Beyond Rust: Rethinking Software Safety in a Legacy World

Last year, 2025, saw another wave of severe security vulnerabilities discovered and patched in major, established software systems—including eight actively exploited zero-day flaws in one of the world’s most widely used browsers. Many of these were classic memory-safety errors, such as use-after-free or out-of-bounds access, which are particularly common in C++-based code.

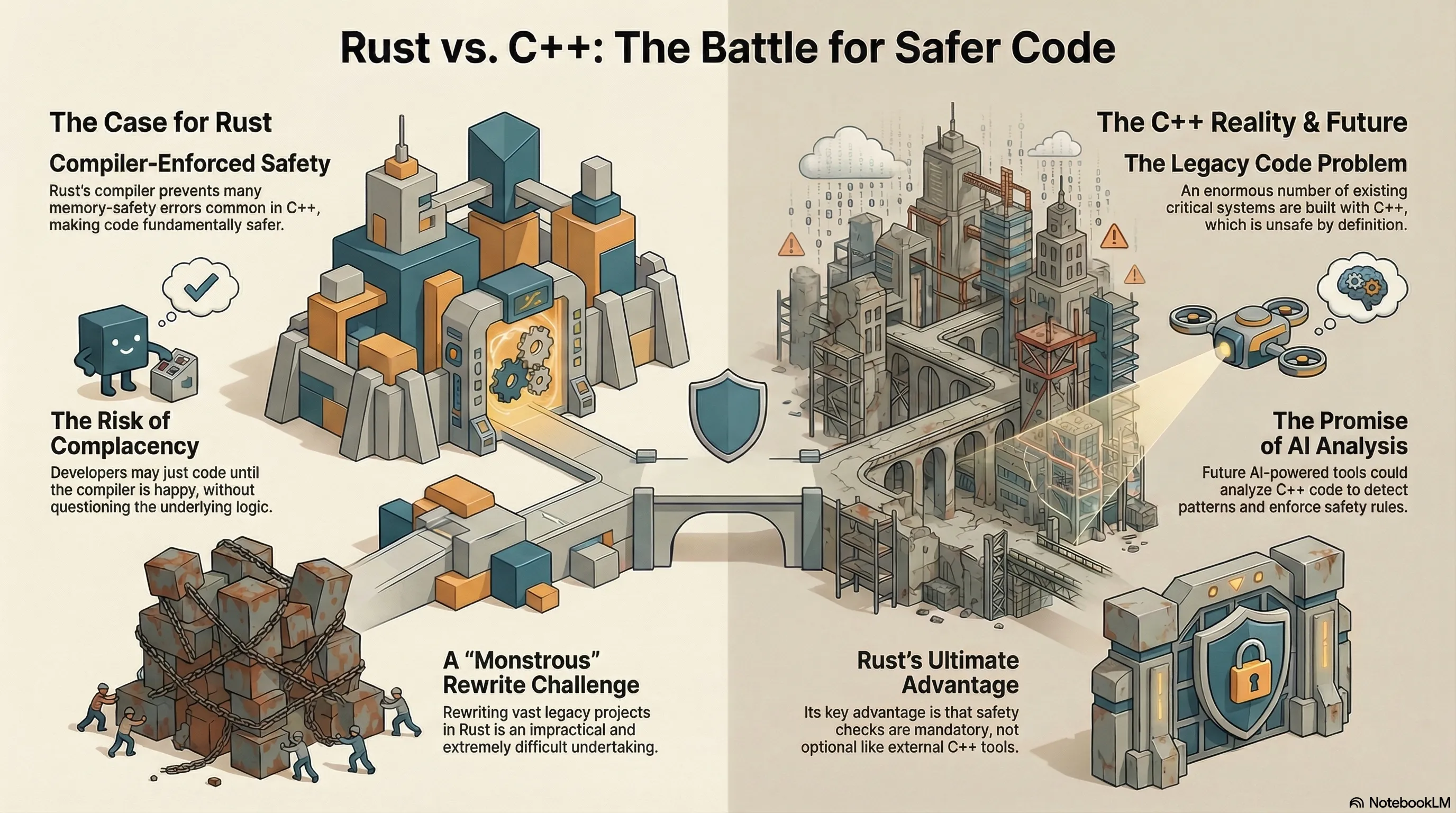

The Promise and Appeal of Rust

Indeed, these incidents represent the kind of errors that, in many cases, could have been avoided by using Rust. I completely understand the call to adopt Rust. I also understand companies that use or want to use Rust for security-critical systems precisely for this reason. I recognize that it would spare us a lot of trouble.

The Obscured, Deeper Problem

However, this perspective seems far too narrow to me and obscures the real issue: superficiality. Projects like major browsers or even entire operating systems are so vast that almost no one can maintain a comprehensive, deep technical overview. Developers come and go. Ensuring consistent output quality is an immense challenge. It’s entirely understandable that the current situation is unsustainable.

Rust’s Compiler-Enforced Safety

Rust is different. Unlike the classic C++, its compiler enforces a certain way of working from the start. That sounds brilliant at first glance. And indeed, such memory-safety errors would be less problematic. Even what happened to Cloudflare in November—which resulted in an outage despite their use of Rust—might have been exploitable in another language, potentially without causing a direct outage.

I don’t want to delve much deeper here. Too many hypotheticals! So, to be clear: Rust—or rather, its compiler—ensures fundamentally safer code. That’s undeniable. A fact. As we’ve seen in recent months, you can still make plenty of mistakes. The impact, at least for these security flaws, is less critical. In the worst case, it crashes. But exploiting such a flaw becomes significantly harder, if not impossible.

The Risk of Complacency

Yet, I observe a problem here similar to “vibe coding”: the assumption that whatever gets “thrown out there” must be correct. With vibe coding, the problem is universal and catches up with you in any language. With Rust, in my view, it means fundamentals and a deep understanding of details can be lost. You end up trying different versions of your code until the compiler is happy. Once it is, the result is often no longer questioned.

When experienced developers use such tools—which Rust also is—it can add value. When an inexperienced junior uses it, things get interesting. Especially when maintaining the code later on. I’m curious whether a clear, logical thread will still be found in such code later.

The Reality of the C++ World

C++, on the other hand, is by definition unsafe. Let’s accept that fact. Just like the fact that an enormous number of systems are currently written in C++. How do we make these secure? One thing is clear: No matter which language a system is built with, such security flaws are never desired or tolerated. So what do we do about them?

The “Rewrite in Rust” Mantra

“Rewrite in Rust” is a common refrain. And you can do that. It’s fine for small projects. For large ones? A monstrous challenge. It’s not just the effort itself. In the end, it still has to do the same thing. A classic modernization problem that everyone is very reluctant to tackle.

Writing Everything New in Rust

Write everything new in Rust. More and more companies are doing this. Significantly safer, because the legacy code continues to serve its purpose for now. Rust can also coexist wonderfully with C++ and other languages. A perfectly legitimate approach. Considering the objections above regarding code quality, the future will tell whether this will truly pay off—or whether costly refactoring will still be needed later.

The Unaddressed Legacy Code

However, both approaches fail to address the vast amount of legacy code that isn’t even considered for a rewrite or modernization. So, what if we simply elevate what already exists to a new level as a whole? C++26 aims precisely in this direction. Although here, one must consciously choose such a path. So C++ remains, by definition, unsafe.

A Future of AI-Powered Analysis

It is already possible today to write absolutely safe C++ code. What’s missing: the one authority that fully controls compliance. In the first instance, static code analysis can detect many such violations. But applied long-term and to large projects, AI could certainly recognize relevant patterns here. Recognizing patterns should be one of AI’s great strengths.

The Role of Rust Now and in the Future

I currently see Rust as an immediate aid because there is no real substitute in its class. Looking ahead, however, I believe we can make even old systems significantly more secure—by using these yet-to-be-created tools to analyze code and enforce safety rules.

The Final Advantage?

And once you’ve created something like that for the C++ world, only one advantage remains for Rust: that this check is

firmly integrated into the compiler, whereas with C++ you could still omit it. Whether this advantage remains decisive

likely depends on how consistently we all—developers, companies, and the community—employ such security tools in

practice. And perhaps also on whether Rust eventually further restricts or even removes unsafe.

Further Explorations

- The Rust Foundation Blog for updates on the language and its ecosystem.

- The ISO C++ Foundation for the latest on C++ standards and developments.

- Memory Safety initiative, focusing on broader approaches to eliminating memory safety vulnerabilities.

- Google’s “The Rule of 2” for a pragmatic framework on writing secure code, regardless of language.